University of Maryland Extension Offers Free Counseling and Guidance for Farm Families

|

An article in the New castle News emphasizes how difficult it is to measure the extent of farm stress and suicide risk, and points out some of the barriers that prevent those at risk from seeking mental health care”

HARRISBURG – Data released in January by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found the national suicide rate for male farmers and ranchers in 2016 was double the rate for all working-age males.

That number, according to the data, is 43.2 per 100,000 for farmers and ranches, compared to 27.4, for everyone else. The finding came days after a Suicide Prevention Task Force created by Gov. Tom Wolf identified the farming community as being a segment of the population at increased risk for suicide.

According to a 2018 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States. In 2017, more than 47,000 individuals died by suicide nationwide, the most recent year for which data was available. In Pennsylvania alone, 2,023 individuals died by suicide that year -- the first time in at least the last quarter-century that there were more than 2,000 suicides in Pennsylvania in a single year, according to suicide data compiled by researchers at the University of Indiana.

Even so, how often suicides happen on Pennsylvania farms is far from clear.

The Pennsylvania Agriculture Department doesn’t have data on how often farmers attempt or commit suicide in this state, said Shannon Powers, a spokeswoman for the agency. The Pennsylvania Farm Bureau has repeatedly asked its members if they are aware of suicides on local farms and has come up empty, said Mark O’Neill, a spokesman for the organization.

“We have reached out to regional directors, county farm bureau representatives and other farmer members on three separate occasions over the past two years and have not heard of a single farmer suicide in the Commonwealth,” O’Neill said. “Does that definitively mean that no farmers in Pennsylvania have committed suicide over the past few years? No. But we do not have any data or direct feedback from anyone.”

The lack of clear data on how pervasive suicide may be in the agriculture community was one of the issues identified by Suicide Prevention Task Force, she said. But state and agriculture officials say that suicide and mental health have emerged as issues affecting the farming industry that need to be confronted.

In a roundtable discussion access to mental health and suicide in the farming community held earlier this month in Beaver County, Pennsylvania Agriculture Secretary Russell Redding said when talking about farming, “We have a tendency to think in business terms, we forget there’s a human being on both sides,” the consumer and the farmer who grows the food.

“We only get to a better place on mental health by talking about it,” he said.

It’s difficult to know how much worse the mental health and suicide risk is getting for farmers or whether it’s getting more attention because people are becoming more comfortable talking about it, said Lisa Davis, director of the Pennsylvania Office of Rural Health. In a roundtable discussion on access to mental health services for farmers held in Beaver County last month, state Sen. Elder Vogel, R-Beaver County, said that there are ample stresses that are impacting farmers now. Those include, “low commodity prices, mounting debt, drought, overwork, government regulation and isolation,” he said, adding, “very little is being done to help them.”

O’Neill said that with the lack of real data on the problem, it’s impossible to know whether there are increasing numbers of farmers dealing with mental health issues.

“There are many factors that can influence the mental well-being of individuals, including farmers. Some of those factors are complex and go beyond simply looking at the financial situation of the individual,” O’Neill said. “It is overly simplistic to conclude that farmers would kill themselves based solely on the fact that their farms are in poor financial situations.”

The Farm Bureau has been working to encourage its members to pay attention to their friends and relatives for signs of depression or suicidal thoughts and encouraging those in crisis to get help, O’Neill said.

Pennsylvania’s suicide hotline number is 1-800-273-8255.

“Our messages have also focused on removing the negative stigma associated with mental health issues to ensure that farmers get the message that there is no shame in seeking help if they have a problem,” O’Neill said. “We also remind farm families that they are not alone and that there are many people in their local community, including other farmers, who care about them and want to help them.”

HARRISBURG – Data released in January by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found the national suicide rate for male farmers and ranchers in 2016 was double the rate for all working-age males.

That number, according to the data, is 43.2 per 100,000 for farmers and ranches, compared to 27.4, for everyone else. The finding came days after a Suicide Prevention Task Force created by Gov. Tom Wolf identified the farming community as being a segment of the population at increased risk for suicide.

According to a 2018 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States. In 2017, more than 47,000 individuals died by suicide nationwide, the most recent year for which data was available. In Pennsylvania alone, 2,023 individuals died by suicide that year -- the first time in at least the last quarter-century that there were more than 2,000 suicides in Pennsylvania in a single year, according to suicide data compiled by researchers at the University of Indiana.

Even so, how often suicides happen on Pennsylvania farms is far from clear.

The Pennsylvania Agriculture Department doesn’t have data on how often farmers attempt or commit suicide in this state, said Shannon Powers, a spokeswoman for the agency. The Pennsylvania Farm Bureau has repeatedly asked its members if they are aware of suicides on local farms and has come up empty, said Mark O’Neill, a spokesman for the organization.

“We have reached out to regional directors, county farm bureau representatives and other farmer members on three separate occasions over the past two years and have not heard of a single farmer suicide in the Commonwealth,” O’Neill said. “Does that definitively mean that no farmers in Pennsylvania have committed suicide over the past few years? No. But we do not have any data or direct feedback from anyone.”

The lack of clear data on how pervasive suicide may be in the agriculture community was one of the issues identified by Suicide Prevention Task Force, she said. But state and agriculture officials say that suicide and mental health have emerged as issues affecting the farming industry that need to be confronted.

In a roundtable discussion access to mental health and suicide in the farming community held earlier this month in Beaver County, Pennsylvania Agriculture Secretary Russell Redding said when talking about farming, “We have a tendency to think in business terms, we forget there’s a human being on both sides,” the consumer and the farmer who grows the food.

“We only get to a better place on mental health by talking about it,” he said.

It’s difficult to know how much worse the mental health and suicide risk is getting for farmers or whether it’s getting more attention because people are becoming more comfortable talking about it, said Lisa Davis, director of the Pennsylvania Office of Rural Health. In a roundtable discussion on access to mental health services for farmers held in Beaver County last month, state Sen. Elder Vogel, R-Beaver County, said that there are ample stresses that are impacting farmers now. Those include, “low commodity prices, mounting debt, drought, overwork, government regulation and isolation,” he said, adding, “very little is being done to help them.”

O’Neill said that with the lack of real data on the problem, it’s impossible to know whether there are increasing numbers of farmers dealing with mental health issues.

“There are many factors that can influence the mental well-being of individuals, including farmers. Some of those factors are complex and go beyond simply looking at the financial situation of the individual,” O’Neill said. “It is overly simplistic to conclude that farmers would kill themselves based solely on the fact that their farms are in poor financial situations.”

The Farm Bureau has been working to encourage its members to pay attention to their friends and relatives for signs of depression or suicidal thoughts and encouraging those in crisis to get help, O’Neill said.

Pennsylvania’s suicide hotline number is 1-800-273-8255.

“Our messages have also focused on removing the negative stigma associated with mental health issues to ensure that farmers get the message that there is no shame in seeking help if they have a problem,” O’Neill said. “We also remind farm families that they are not alone and that there are many people in their local community, including other farmers, who care about them and want to help them.”

Another Possible Toll…Trade Wars: Farmer Suicides

Mounting financial stress could further push the grim tally in rural America.

From The Washington Post

Rural suicides in the U.S. have climbed significantly in recent years, and farm leaders and mental health care providers say the financial toll…trade wars could contribute to the tragedy.

An official of the National Farmers Union warned earlier this year that financial stress, including the added burden of disappearing markets in the trade war, appear to be taking a toll on farmers’ mental health.

“It’s been insane,” Patty Edelburg, vice president of the organization that represents some 200,000 families, said on Fox News. “We’ve had a lot more bankruptcies going on, a lot more farmer suicides.”

She said the trade war with China could contribute to financial stress.

“We have more commodities, more grain sitting on the ground right now because we lost huge export markets,” she said. “We’ve lost export markets that we’ve had for 30 years that we’ll never get a chance to get back again.”

A new survey published this month in the Journal of the American Medical Association Network Open …covering the years from 1999 to 2016, found that the rate of suicide among Americans ages 25 to 64 rose by 41% in that time. Rates among those living in rural counties were 25% higher than people in major metropolitan areas.

Researchers suspect the increase is related to poverty, lower incomes and underemployment. “Those factors are really bad in rural areas,” study author Danielle Steelesmith, a postdoctoral fellow at Ohio State University’s Wexner Medical Center, told NBC.

The study also found that counties with high levels of social fragmentation — based on the levels of single-person households, unmarried residents and transient residents — and a high percentage of veterans had higher rates of suicide. All of those factors were more pronounced in rural counties. And farmers have voiced concern that…trade wars could exacerbate tough financial conditions for them.

“With these added tariffs, farmers are not getting their [credit] lines renewed, banks are coming in and foreclosing on their farms, taking their family living away, and it’s too much for some of them,” Minnesota soybean farmer Bill Gordon told CNN earlier this year. “We have seen a definite increase in the suicide rate and depression in farmers in the U.S.”

Wisconsin had a record 915 suicides in 2017, many of them farmers under financial stress. Net farm income has plunged 50% in six years.

Farm help organization Farm Aid reported a 30% increase last year in calls to its hotline.

The calls and “our work with partners around the country confirm that farmers are under incredible financial, legal and emotional stress. Bankruptcies, foreclosures, depression and even suicide are some of the tragic consequences of these pressures,” said a statement from the organization.

“America’s family farmers — reduced in numbers since the farm crisis of the 1980s — have approached endangered status. ... At Farm Aid, we spend our time on the phone with anxious farm families who cannot make ends meet, and who will not be able to improve their situation simply by working harder. Confusion and lack of resolution on policies like trade, immigration and healthcare accelerate the crisis.”

Mike Rosmann, a therapist who helps suicidal farmers, blames the stresses of surviving on the land for farmers who can’t take it anymore. Low farm prices, the “prolonged recession in agriculture,” flooding and the Trump administration are all causing problems, he wrote in an April column in The New Republic. “Farmers are becoming dismayed about the tariffs.”

A Morning Consult and American Farm Bureau Federation research poll published in April found that 91% of farmers and farmworkers said financial issues are affecting their mental health. About 87% of those surveyed said they fear losing their farms.

Rural suicides in the U.S. have climbed significantly in recent years, and farm leaders and mental health care providers say the financial toll…trade wars could contribute to the tragedy.

An official of the National Farmers Union warned earlier this year that financial stress, including the added burden of disappearing markets in the trade war, appear to be taking a toll on farmers’ mental health.

“It’s been insane,” Patty Edelburg, vice president of the organization that represents some 200,000 families, said on Fox News. “We’ve had a lot more bankruptcies going on, a lot more farmer suicides.”

She said the trade war with China could contribute to financial stress.

“We have more commodities, more grain sitting on the ground right now because we lost huge export markets,” she said. “We’ve lost export markets that we’ve had for 30 years that we’ll never get a chance to get back again.”

A new survey published this month in the Journal of the American Medical Association Network Open …covering the years from 1999 to 2016, found that the rate of suicide among Americans ages 25 to 64 rose by 41% in that time. Rates among those living in rural counties were 25% higher than people in major metropolitan areas.

Researchers suspect the increase is related to poverty, lower incomes and underemployment. “Those factors are really bad in rural areas,” study author Danielle Steelesmith, a postdoctoral fellow at Ohio State University’s Wexner Medical Center, told NBC.

The study also found that counties with high levels of social fragmentation — based on the levels of single-person households, unmarried residents and transient residents — and a high percentage of veterans had higher rates of suicide. All of those factors were more pronounced in rural counties. And farmers have voiced concern that…trade wars could exacerbate tough financial conditions for them.

“With these added tariffs, farmers are not getting their [credit] lines renewed, banks are coming in and foreclosing on their farms, taking their family living away, and it’s too much for some of them,” Minnesota soybean farmer Bill Gordon told CNN earlier this year. “We have seen a definite increase in the suicide rate and depression in farmers in the U.S.”

Wisconsin had a record 915 suicides in 2017, many of them farmers under financial stress. Net farm income has plunged 50% in six years.

Farm help organization Farm Aid reported a 30% increase last year in calls to its hotline.

The calls and “our work with partners around the country confirm that farmers are under incredible financial, legal and emotional stress. Bankruptcies, foreclosures, depression and even suicide are some of the tragic consequences of these pressures,” said a statement from the organization.

“America’s family farmers — reduced in numbers since the farm crisis of the 1980s — have approached endangered status. ... At Farm Aid, we spend our time on the phone with anxious farm families who cannot make ends meet, and who will not be able to improve their situation simply by working harder. Confusion and lack of resolution on policies like trade, immigration and healthcare accelerate the crisis.”

Mike Rosmann, a therapist who helps suicidal farmers, blames the stresses of surviving on the land for farmers who can’t take it anymore. Low farm prices, the “prolonged recession in agriculture,” flooding and the Trump administration are all causing problems, he wrote in an April column in The New Republic. “Farmers are becoming dismayed about the tariffs.”

A Morning Consult and American Farm Bureau Federation research poll published in April found that 91% of farmers and farmworkers said financial issues are affecting their mental health. About 87% of those surveyed said they fear losing their farms.

A Season of Loss on a family farm

“As his crop fields flooded and global trade wars dragged on, (name withheld) was racked with debt and despair. His death reflects a worrying trend in farm country, where calls to suicide hotlines are on the rise.”

A November 10th front page article in the Washington Post included some alarming facts:

Farmers across the nation face increasing debt loads, and farm bankruptcies nationally are up 24% since September 2018. Economic pressure is greater for farmers in particular geographic areas and in particular agricultural segments. Grain farmers in Minnesota, Nebraska, South Dakota and Wisconsin face more difficult conditions than other farmers, largely because they are dependent on global commodity trade and trade wars with Canada, Mexico and China have driven commodity prices down. Farm debt, bankruptcies and suicides are up in those states.

In 2018, Wisconsin lost 700 dairy farmers, and the number of dairy cattle has fallen by 40%. Over 2,700 dairy farms closed nationwide. National Farm Union President Roger Johnson said “There has got to be some sort of a government incentive for dairy producers to produce less milk…Nobody wants to call it supply management, but that's what it is." Keeping in mind that farmers are paid according to the volume their herds produce, this is a daunting statement for family dairy farmers.

On Delmarva, where Save a Shore Farmer focuses, falling commodity prices affect those farms that produce grain for poultry feed. To some extent local farmers are insulated from national trends. The president of a major poultry processing company with contracts with hundreds of local farmers told us that farmers on the Eastern shore are paid commodity prices plus a bonus that reflects lower transport costs for the local processing firms. Nonetheless, lower commodity prices, even though driven by forces outside Delmarva, mean lower income and profits.

Many states have increased mental health funding for services for rural communities while rural hospitals close at a faster pace, leaving rural communities even more distant from healthcare facilities. There are mental health resources available in farm country, but the stigma against seeking help for psychiatric disorders prevents many farmers from reaching out for help. The purpose of Save a Shore Farmer is to chip away at the stigma, to make it clear that there is no shame in asking for help.

A November 10th front page article in the Washington Post included some alarming facts:

- In farm country, mental health experts say they’re seeing more suicides as families endure the worst period for U.S. agriculture in decades.

- Farm bankruptcies and loan delinquencies are rising…profits are vanishing during President Trump’s trade disputes.

- In South Dakota (ed. note: where the farm suicide chronicled in the article occurred) calls to the nationwide suicide hotline were up 61 percent last year.

- In 2016 (ed. note: when the South Dakota farmer took over the family farm) corn sold for $5 a bushel and soybeans more than $13 a bushel…The week he died, corn was at $3.73 a bushel and soybeans at $7.50 a bushel.

- …trade disputes and extreme weather have devastated farmers and ranchers – often isolated with little access to services.

Farmers across the nation face increasing debt loads, and farm bankruptcies nationally are up 24% since September 2018. Economic pressure is greater for farmers in particular geographic areas and in particular agricultural segments. Grain farmers in Minnesota, Nebraska, South Dakota and Wisconsin face more difficult conditions than other farmers, largely because they are dependent on global commodity trade and trade wars with Canada, Mexico and China have driven commodity prices down. Farm debt, bankruptcies and suicides are up in those states.

In 2018, Wisconsin lost 700 dairy farmers, and the number of dairy cattle has fallen by 40%. Over 2,700 dairy farms closed nationwide. National Farm Union President Roger Johnson said “There has got to be some sort of a government incentive for dairy producers to produce less milk…Nobody wants to call it supply management, but that's what it is." Keeping in mind that farmers are paid according to the volume their herds produce, this is a daunting statement for family dairy farmers.

On Delmarva, where Save a Shore Farmer focuses, falling commodity prices affect those farms that produce grain for poultry feed. To some extent local farmers are insulated from national trends. The president of a major poultry processing company with contracts with hundreds of local farmers told us that farmers on the Eastern shore are paid commodity prices plus a bonus that reflects lower transport costs for the local processing firms. Nonetheless, lower commodity prices, even though driven by forces outside Delmarva, mean lower income and profits.

Many states have increased mental health funding for services for rural communities while rural hospitals close at a faster pace, leaving rural communities even more distant from healthcare facilities. There are mental health resources available in farm country, but the stigma against seeking help for psychiatric disorders prevents many farmers from reaching out for help. The purpose of Save a Shore Farmer is to chip away at the stigma, to make it clear that there is no shame in asking for help.

SHRINKING MARKETS MEAN MORE FARMER STRESS, SUICIDES

Rural suicides in the U.S. have climbed significantly in recent years, and farm leaders and mental health care providers say the financial toll of trade wars could contribute to the tragedy.

An official of the National Farmers Union warned earlier this year that financial stress, including the added burden of disappearing markets in the trade war, appear to be taking a toll on farmers’ mental health.

“It’s been insane,” Patty Edelburg, vice president of the organization that represents some 200,000 families, said in May. “We’ve had a lot more bankruptcies going on, a lot more farmer suicides.” She said the trade war with China could contribute to financial stress.

“We have more commodities, more grain sitting on the ground right now because we lost huge export markets,” she said. “We’ve lost export markets that we’ve had for 30 years that we’ll never get a chance to get back again.”

A new survey published this month in the Journal of the American Medical Asociation covering the years from 1999 to the election of 2016, found that the rate of suicide among Americans ages 25 to 64 rose by 41% in that time. Rates among those living in rural counties were 25% higher than people in major metropolitan areas.

Researchers suspect the increase is related to poverty, lower incomes and underemployment. “Those factors are really bad in rural areas,” study author Danielle Steelesmith, a postdoctoral fellow at Ohio State University’s Wexner Medical Center, told NBC.

The study also found that counties with high levels of social fragmentation — based on the levels of single-person households, unmarried residents and transient residents — and a high percentage of veterans had higher rates of suicide. All of those factors were more pronounced in rural counties. Farmers have voiced concern that trade wars could exacerbate tough financial conditions for them.

“With these added tariffs, farmers are not getting their [credit] lines renewed, banks are coming in and foreclosing on their farms, taking their family living away, and it’s too much for some of them,” Minnesota soybean farmer Bill Gordon told CNN earlier this year. “We have seen a definite increase in the suicide rate and depression in farmers in the U.S.”

Wisconsin had a record 915 suicides in 2017, many of them farmers under financial stress. Net farm income has plunged 50% in six years.

Farm help organization Farm Aid reported a 30% increase last year in calls to its hotline. The calls and “our work with partners around the country confirm that farmers are under incredible financial, legal and emotional stress. Bankruptcies, foreclosures, depression and even suicide are some of the tragic consequences of these pressures,” said a statement from the organization.

“America’s family farmers — reduced in numbers since the farm crisis of the 1980s — have approached endangered status. ... At Farm Aid, we spend our time on the phone with anxious farm families who cannot make ends meet, and who will not be able to improve their situation simply by working harder. Confusion and lack of resolution on policies like trade, immigration and healthcare accelerate the crisis.”

Mike Rosmann, a therapist who helps suicidal farmers, blames the stresses of surviving on the land for farmers who can’t take it anymore. Low farm prices, the “prolonged recession in agriculture,” flooding, and the trade wars and tariffs are all causing problems, he wrote in an April column in The New Republic. “Farmers are becoming dismayed about the tariffs.”

A Morning Consult and American Farm Bureau Federation research poll published in April found that 91% of farmers and farmworkers said financial issues are affecting their mental health. About 87% of those surveyed said they fear losing their farms.

An official of the National Farmers Union warned earlier this year that financial stress, including the added burden of disappearing markets in the trade war, appear to be taking a toll on farmers’ mental health.

“It’s been insane,” Patty Edelburg, vice president of the organization that represents some 200,000 families, said in May. “We’ve had a lot more bankruptcies going on, a lot more farmer suicides.” She said the trade war with China could contribute to financial stress.

“We have more commodities, more grain sitting on the ground right now because we lost huge export markets,” she said. “We’ve lost export markets that we’ve had for 30 years that we’ll never get a chance to get back again.”

A new survey published this month in the Journal of the American Medical Asociation covering the years from 1999 to the election of 2016, found that the rate of suicide among Americans ages 25 to 64 rose by 41% in that time. Rates among those living in rural counties were 25% higher than people in major metropolitan areas.

Researchers suspect the increase is related to poverty, lower incomes and underemployment. “Those factors are really bad in rural areas,” study author Danielle Steelesmith, a postdoctoral fellow at Ohio State University’s Wexner Medical Center, told NBC.

The study also found that counties with high levels of social fragmentation — based on the levels of single-person households, unmarried residents and transient residents — and a high percentage of veterans had higher rates of suicide. All of those factors were more pronounced in rural counties. Farmers have voiced concern that trade wars could exacerbate tough financial conditions for them.

“With these added tariffs, farmers are not getting their [credit] lines renewed, banks are coming in and foreclosing on their farms, taking their family living away, and it’s too much for some of them,” Minnesota soybean farmer Bill Gordon told CNN earlier this year. “We have seen a definite increase in the suicide rate and depression in farmers in the U.S.”

Wisconsin had a record 915 suicides in 2017, many of them farmers under financial stress. Net farm income has plunged 50% in six years.

Farm help organization Farm Aid reported a 30% increase last year in calls to its hotline. The calls and “our work with partners around the country confirm that farmers are under incredible financial, legal and emotional stress. Bankruptcies, foreclosures, depression and even suicide are some of the tragic consequences of these pressures,” said a statement from the organization.

“America’s family farmers — reduced in numbers since the farm crisis of the 1980s — have approached endangered status. ... At Farm Aid, we spend our time on the phone with anxious farm families who cannot make ends meet, and who will not be able to improve their situation simply by working harder. Confusion and lack of resolution on policies like trade, immigration and healthcare accelerate the crisis.”

Mike Rosmann, a therapist who helps suicidal farmers, blames the stresses of surviving on the land for farmers who can’t take it anymore. Low farm prices, the “prolonged recession in agriculture,” flooding, and the trade wars and tariffs are all causing problems, he wrote in an April column in The New Republic. “Farmers are becoming dismayed about the tariffs.”

A Morning Consult and American Farm Bureau Federation research poll published in April found that 91% of farmers and farmworkers said financial issues are affecting their mental health. About 87% of those surveyed said they fear losing their farms.

FARM SUICIDE PREVENTION CAMPAIGN ANNOUNCES ITS SECOND YEAR

When “Save a Shore Farmer” billboards went up on Route 13 last fall, and when televised public service announcements were screened, it was obvious that the suicide prevention campaign had struck a chord.

The Jesse Klump Suicide Awareness & Prevention Program has received a second grant from the Rural Maryland Council that will fund most of an expanded year two of Save a Shore Farmer.

“The CDC released a report that concluded that the occupation subgroup composed of farmers, forestry workers and commercial fishermen ranks #4 on a list of suicide risk by occupation,” said Fund President Kim Klump. “It didn’t take us long to realize how important those industries are to our communities, especially farming, and when a grant opportunity arose we were prepared to take advantage of it to launch this new campaign.”

Save a Shore Farmer’s first year focused on intensive media outreach, to raise awareness of the heightened risk of suicide in farm families and to spread the message that suicide can be prevented. This included billboard placement, over 1,000 television spots, placing printed information at 19 sites in the lower three counties where farmers may gather, and appearances at agricultural related events. The second year will expand upon that work, and include Spanish language versions of the material.

“The first indication that we were reaching people was the spike we observed in visits to www.saveashorefarmer.org, the website created especially for the campaign, after billboards went up and after television spots began,” Klump said. “In year two we hope to engage farm families more directly, teaching recognition of the warning signs of suicide’s threat. We’re open to any suggestions about events relating to farming where we may exhibit, organizations that would invite us to speak, or any way to reach the agricultural population.”

Another result was invitations to present at both the Maryland Suicide Prevention Conference and the Maryland Rural Health Association Conference. “These sessions will be a great opportunity to showcase the innovative and collaborative suicide prevention work from our area to partners across the state,” said Worcester County Health Planner Jackie Ward. The Jesse Klump Memorial Fund and the Health Department are members of the Suicide Prevention Coalition serving the lower Eastern Shore, a consortium of many groups, governmental, private and nonprofit, working to enhance mental health care and reduce suicide rates.

Save a Shore Farmer attracted attention from beyond Maryland’s borders. The University of Minnesota’s Rural Health Center wrote that Save a Shore Farmer is “…one of a handful of exemplar models of rural suicide prevention programs from across the country.”

To learn more about the risk of suicide among farmers, the whys and wherefores, to find resources for anyone about whom you may be concerned, or to explore ways that you or an organization you know can participate in the campaign, visit www.saveashorefarmer.org.

The Jesse Klump Suicide Awareness & Prevention Program has received a second grant from the Rural Maryland Council that will fund most of an expanded year two of Save a Shore Farmer.

“The CDC released a report that concluded that the occupation subgroup composed of farmers, forestry workers and commercial fishermen ranks #4 on a list of suicide risk by occupation,” said Fund President Kim Klump. “It didn’t take us long to realize how important those industries are to our communities, especially farming, and when a grant opportunity arose we were prepared to take advantage of it to launch this new campaign.”

Save a Shore Farmer’s first year focused on intensive media outreach, to raise awareness of the heightened risk of suicide in farm families and to spread the message that suicide can be prevented. This included billboard placement, over 1,000 television spots, placing printed information at 19 sites in the lower three counties where farmers may gather, and appearances at agricultural related events. The second year will expand upon that work, and include Spanish language versions of the material.

“The first indication that we were reaching people was the spike we observed in visits to www.saveashorefarmer.org, the website created especially for the campaign, after billboards went up and after television spots began,” Klump said. “In year two we hope to engage farm families more directly, teaching recognition of the warning signs of suicide’s threat. We’re open to any suggestions about events relating to farming where we may exhibit, organizations that would invite us to speak, or any way to reach the agricultural population.”

Another result was invitations to present at both the Maryland Suicide Prevention Conference and the Maryland Rural Health Association Conference. “These sessions will be a great opportunity to showcase the innovative and collaborative suicide prevention work from our area to partners across the state,” said Worcester County Health Planner Jackie Ward. The Jesse Klump Memorial Fund and the Health Department are members of the Suicide Prevention Coalition serving the lower Eastern Shore, a consortium of many groups, governmental, private and nonprofit, working to enhance mental health care and reduce suicide rates.

Save a Shore Farmer attracted attention from beyond Maryland’s borders. The University of Minnesota’s Rural Health Center wrote that Save a Shore Farmer is “…one of a handful of exemplar models of rural suicide prevention programs from across the country.”

To learn more about the risk of suicide among farmers, the whys and wherefores, to find resources for anyone about whom you may be concerned, or to explore ways that you or an organization you know can participate in the campaign, visit www.saveashorefarmer.org.

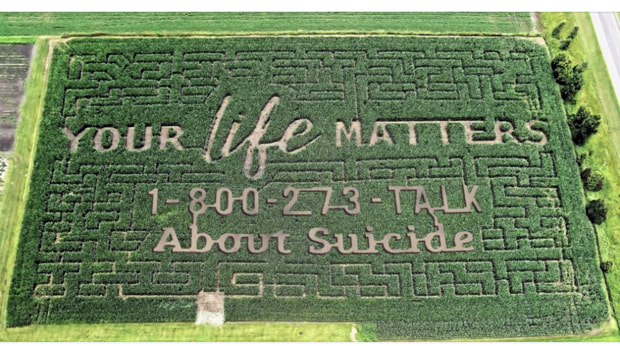

SUICIDE PREVENTION HOTINE CARVED INTO THIS FAMILY’S CORN MAZE

From CBS News:

"Your life matters." That is the message a family of farmers from Menomonie, Wisconsin wants the world to know. The Govin family always carves a unique message into their farm's corn maze. This summer, they carved an important one: information for the National Suicide Prevention Hotline.

Govin's Meats & Berries shared an image of their new corn maze on Facebook, with a simple explanation behind its meaning. "We have always picked a theme that has meaning to our family and this year suicide was something we unfortunately had to face and learn about," the family wrote. "We hope to make a difference in someone's life and help them understand that they matter!"

In addition to the "your life matters" message, the corn maze also includes the National Suicide Prevention Hotline number: 1-800-273-TALK. The same number was the subject of a 2017 song by Logic and Alessia Cara. The name of the song was the number.

That song made it to the Billboard Hot 100 and was performed at the Grammys, but the corn maze is getting widespread attention, too. The image received more than 1,000 shares on social media and several positive comments. "Incredible!! This is awesome! You guys are such wonderful people!" one person wrote.

In the past, the Govins' corn maze has been NFL themed, Valentine's Day themed, and even Garth Brooks themed. But this one had the greatest significance: to raise awareness for suicide prevention.

John Govin, who owns the farm with his wife, Julie, said coming up with the idea was easy — but going through with it was not. "Fall is a fun time," Govin told WQOW. "You're really celebrating a harvest, you're celebrating everything that was good all summer long. And then to choose to do something like this … is it gonna drive people to your farm, or is it gonna drive them away?"

The Govins said it was worth the risk. "On the way to the family funeral, we both realized that this is just so much more than just trying to drive people to our farm," he said.

"Everybody is somebody's most important person," he told WQOW, choking back tears. "If we can make a difference, if we save a life this fall… that's worth it."

"Your life matters." That is the message a family of farmers from Menomonie, Wisconsin wants the world to know. The Govin family always carves a unique message into their farm's corn maze. This summer, they carved an important one: information for the National Suicide Prevention Hotline.

Govin's Meats & Berries shared an image of their new corn maze on Facebook, with a simple explanation behind its meaning. "We have always picked a theme that has meaning to our family and this year suicide was something we unfortunately had to face and learn about," the family wrote. "We hope to make a difference in someone's life and help them understand that they matter!"

In addition to the "your life matters" message, the corn maze also includes the National Suicide Prevention Hotline number: 1-800-273-TALK. The same number was the subject of a 2017 song by Logic and Alessia Cara. The name of the song was the number.

That song made it to the Billboard Hot 100 and was performed at the Grammys, but the corn maze is getting widespread attention, too. The image received more than 1,000 shares on social media and several positive comments. "Incredible!! This is awesome! You guys are such wonderful people!" one person wrote.

In the past, the Govins' corn maze has been NFL themed, Valentine's Day themed, and even Garth Brooks themed. But this one had the greatest significance: to raise awareness for suicide prevention.

John Govin, who owns the farm with his wife, Julie, said coming up with the idea was easy — but going through with it was not. "Fall is a fun time," Govin told WQOW. "You're really celebrating a harvest, you're celebrating everything that was good all summer long. And then to choose to do something like this … is it gonna drive people to your farm, or is it gonna drive them away?"

The Govins said it was worth the risk. "On the way to the family funeral, we both realized that this is just so much more than just trying to drive people to our farm," he said.

"Everybody is somebody's most important person," he told WQOW, choking back tears. "If we can make a difference, if we save a life this fall… that's worth it."

FARMERS’ SHARE OF CONSUMER FOOD DOLLAR DECLINES

From a report by Jacqui Fatka at feedstuffs.com

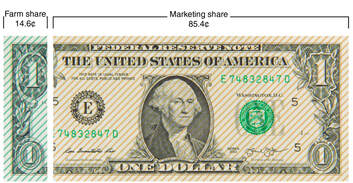

For every dollar American consumers spend on food, U.S. farmers and ranchers earn just 14.6 cents, according to a report released recently by the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Economic Research Service (ERS).

This value for 2017 marks a 17% decline since 2011 and is the smallest portion of the American food dollar farmers have received since USDA began reporting these data in 1993. The remaining 85.4 cents cover off-farm costs, including processing, wholesaling, distribution, marketing and retailing.

“Even though family farmers and ranchers are more productive today than they have ever been, they’re taking home a smaller and smaller portion of the American food dollar,” National Farmers Union president Roger Johnson said.

Since the previous year, farm production costs per food dollar remained constant at 7.8 cents in 2017 and are still at their lowest level since 2002. Foodservice costs per food dollar rose to 36.7 cents in 2017, increasing for the ninth consecutive year since 2008, when these costs were 29.0 cents. Food packaging costs were 2.3 cents in 2017, an all-time low since the beginning of this series; packaging costs were recorded at their highest level of 4.2 cents in 2002.

Although 2017 was the sixth consecutive year the farm share dropped, the decline was smaller than in 2016 (4.5%) and 2015 (9.9%). Unlike in the previous two years, average prices received by U.S. farmers went up in 2017, as measured by the Producer Price Index for farm products.

The decline in farm share also coincides with six consecutive years of increases in the share of the food dollar going to the foodservice industry. Increases in food-away-from-home spending by consumers drives down the farm share of the food dollar. “Farmers receive a smaller percentage from eating-out expenditures because food makes up a smaller share of total costs due to restaurants’ added costs for preparing and serving meals,” ERS said.

Johnson said the data don’t paint the full picture of the farm economy, “but when considered in the context of depressed commodity prices, plummeting incomes, rising input costs and deteriorating credit conditions, it is certainly clear that we are in the midst of an agricultural financial crisis.”

Johnson added, “Conditions for farmers have been eroding since 2011, and there’s only so much longer they can hold on. Many have already made the heartbreaking decision to close up shop; in just the past five years, the United States lost upwards of 70,000 farm operations. As a country with a growing population and growing nutritional needs, we can’t afford to lose many more. We sincerely hope this startling report will open policy-makers’ eyes to the financial challenges family farmers and ranchers endure on a daily basis and convince them to provide the support they so desperately need.”

For every dollar American consumers spend on food, U.S. farmers and ranchers earn just 14.6 cents, according to a report released recently by the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Economic Research Service (ERS).

This value for 2017 marks a 17% decline since 2011 and is the smallest portion of the American food dollar farmers have received since USDA began reporting these data in 1993. The remaining 85.4 cents cover off-farm costs, including processing, wholesaling, distribution, marketing and retailing.

“Even though family farmers and ranchers are more productive today than they have ever been, they’re taking home a smaller and smaller portion of the American food dollar,” National Farmers Union president Roger Johnson said.

Since the previous year, farm production costs per food dollar remained constant at 7.8 cents in 2017 and are still at their lowest level since 2002. Foodservice costs per food dollar rose to 36.7 cents in 2017, increasing for the ninth consecutive year since 2008, when these costs were 29.0 cents. Food packaging costs were 2.3 cents in 2017, an all-time low since the beginning of this series; packaging costs were recorded at their highest level of 4.2 cents in 2002.

Although 2017 was the sixth consecutive year the farm share dropped, the decline was smaller than in 2016 (4.5%) and 2015 (9.9%). Unlike in the previous two years, average prices received by U.S. farmers went up in 2017, as measured by the Producer Price Index for farm products.

The decline in farm share also coincides with six consecutive years of increases in the share of the food dollar going to the foodservice industry. Increases in food-away-from-home spending by consumers drives down the farm share of the food dollar. “Farmers receive a smaller percentage from eating-out expenditures because food makes up a smaller share of total costs due to restaurants’ added costs for preparing and serving meals,” ERS said.

Johnson said the data don’t paint the full picture of the farm economy, “but when considered in the context of depressed commodity prices, plummeting incomes, rising input costs and deteriorating credit conditions, it is certainly clear that we are in the midst of an agricultural financial crisis.”

Johnson added, “Conditions for farmers have been eroding since 2011, and there’s only so much longer they can hold on. Many have already made the heartbreaking decision to close up shop; in just the past five years, the United States lost upwards of 70,000 farm operations. As a country with a growing population and growing nutritional needs, we can’t afford to lose many more. We sincerely hope this startling report will open policy-makers’ eyes to the financial challenges family farmers and ranchers endure on a daily basis and convince them to provide the support they so desperately need.”

FARMERS FIRST: A SENATE BILL TO INCREASE RURAL MENTAL HEALTHCARE

In April, Senator Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) and Senator Joni Ernst (R-IA) introduced the bi-partisan “Facilitating Accessible Resources for Mental Health and Encouraging Rural Solutions for Immediate Response to Stressful Times (FARMERS FIRST)” bill.

FARMERS FIRST was introduced in the US Senate in April but there has been no action since. Contact your Senators t urge that the bill, and the funding to accompany it,move forward now.

FARMERS FIRST would reauthorize the Farm and Ranch Stress Assistance Network (FRSAN), which was created by the 2008 Farm Bill but was never funded. Unlike the House bill, the Senate version includes a funding amount ($50 million) for the program. Funding will enable the FRSAN to provide grants to extension services and nonprofit organizations that offer stress assistance programs to individuals engaged in farming, ranching, and other agriculture-related occupations.

Farm Aid is proud to support this important piece of legislation. “With net farm income cut in half over the last five years, rural stress levels are dangerously high. We cannot afford to lose one more farmer. This bill is a crucial first step to create a strong safety net for America’s family farmers,” said Farm Aid executive director Carolyn Mugar. “We urge Congress to come together and act immediately in a positive and preventative way to get help to the countryside. Farmers and the future of our food depend on it.”

“The continued slump in milk prices is creating both economic and emotional stress for dairy farmers, which is why we support the continuation of the Farm and Ranch Stress Assistance Network and the FARMERS FIRST Act, sponsored by Senators Baldwin and Ernst. We hope to see it move forward as part of the 2018 Farm Bill.” – Jim Mulhern, President and CEO, National Milk Producers Federation

“Farmers are facing uncertain times and need adequate services to deal with this mounting stress in the industry. The resources provided by Senators Baldwin, Ernst, Moran, and Heitkamp’s FARMERS FIRST Act provide tools farmers need to manage these difficulties, allowing them to connect with all the resources at their disposal. I thank the Senators for introducing this vital legislation,” – Jon Doggett, Executive Vice President, National Corn Growers Association

“We urge Congress to come together and act immediately in a positive and preventative way to get help to the countryside. Farmers and the future of our food depend on it.” “For those in rural areas seeking mental health services, they face two giant obstacles: availability and accessibility. In 55% of all American counties, most of which are rural, there is not a single psychologist, psychiatrist or social worker. The Farm and Ranch Stress Assistance Network (FRSAN) could help support agricultural workers and their families in rural communities by providing at-home resources for mental health services. As rural communities and economies struggle to come back from the Great Recession, many in the agriculture industry who have experienced little recovery are at higher risk of substance abuse and suicide. We applaud the bipartisan work of our rural health advocates in introducing legislation to provide a key resource for those at risk.” – Jessica Seigel, National Rural Health Association

“The National Farm Medicine Center shares the goals of FARMERS FIRST Act co-sponsors in wanting to increase access to mental health care for the farm and ranch populations, who are subject to such unpredictable and unfavorable economic and environmental stressors.” – Josie Rudolphi, PhD, National Farm Medicine Center

FARMERS FIRST was introduced in the US Senate in April but there has been no action since. Contact your Senators t urge that the bill, and the funding to accompany it,move forward now.

FARMERS FIRST would reauthorize the Farm and Ranch Stress Assistance Network (FRSAN), which was created by the 2008 Farm Bill but was never funded. Unlike the House bill, the Senate version includes a funding amount ($50 million) for the program. Funding will enable the FRSAN to provide grants to extension services and nonprofit organizations that offer stress assistance programs to individuals engaged in farming, ranching, and other agriculture-related occupations.

Farm Aid is proud to support this important piece of legislation. “With net farm income cut in half over the last five years, rural stress levels are dangerously high. We cannot afford to lose one more farmer. This bill is a crucial first step to create a strong safety net for America’s family farmers,” said Farm Aid executive director Carolyn Mugar. “We urge Congress to come together and act immediately in a positive and preventative way to get help to the countryside. Farmers and the future of our food depend on it.”

“The continued slump in milk prices is creating both economic and emotional stress for dairy farmers, which is why we support the continuation of the Farm and Ranch Stress Assistance Network and the FARMERS FIRST Act, sponsored by Senators Baldwin and Ernst. We hope to see it move forward as part of the 2018 Farm Bill.” – Jim Mulhern, President and CEO, National Milk Producers Federation

“Farmers are facing uncertain times and need adequate services to deal with this mounting stress in the industry. The resources provided by Senators Baldwin, Ernst, Moran, and Heitkamp’s FARMERS FIRST Act provide tools farmers need to manage these difficulties, allowing them to connect with all the resources at their disposal. I thank the Senators for introducing this vital legislation,” – Jon Doggett, Executive Vice President, National Corn Growers Association

“We urge Congress to come together and act immediately in a positive and preventative way to get help to the countryside. Farmers and the future of our food depend on it.” “For those in rural areas seeking mental health services, they face two giant obstacles: availability and accessibility. In 55% of all American counties, most of which are rural, there is not a single psychologist, psychiatrist or social worker. The Farm and Ranch Stress Assistance Network (FRSAN) could help support agricultural workers and their families in rural communities by providing at-home resources for mental health services. As rural communities and economies struggle to come back from the Great Recession, many in the agriculture industry who have experienced little recovery are at higher risk of substance abuse and suicide. We applaud the bipartisan work of our rural health advocates in introducing legislation to provide a key resource for those at risk.” – Jessica Seigel, National Rural Health Association

“The National Farm Medicine Center shares the goals of FARMERS FIRST Act co-sponsors in wanting to increase access to mental health care for the farm and ranch populations, who are subject to such unpredictable and unfavorable economic and environmental stressors.” – Josie Rudolphi, PhD, National Farm Medicine Center

Area Farmers Ready To Leave Difficult 2018 Behind

The Dispatch:

December 6th, 2018- By Charlene Sharpe

BERLIN – Wet weather, followed by small yields and low prices, made the year a challenging one for local farmers.

December 6th, 2018- By Charlene Sharpe

BERLIN – Wet weather, followed by small yields and low prices, made the year a challenging one for local farmers.

Is the Second Farm Crisis Upon Us?

Farmers across the country are in a state of emergency with dairy and grain producers, new farmers, and farmers of color being hit the hardest.

September News Article

| September News Article | |

| File Size: | 670 kb |

| File Type: | doc |

September 2018, COLLEGE PARK, Md. — It’s a stressful time in agriculture, in almost any direction you turn. Farm families are feeling the impacts of an inconsistent and unreliable economy; declining incomes, several years of low commodity prices, and increasing costs have worsened debt issues for many operations.

Farmers are facing the decision to parcel off their land, file for bankruptcy, and take secondary jobs off the farm to provide supplemental income.

The University of Maryland Extension last month launched a new web page devoted to assisting farm families in dealing with stress management through difficult economic times. The Farm Stress Management website, located at https://extension.umd.edu/FarmStressManagement, was released in conjunction with National Suicide Prevention week on Sept. 9-15.

It is a set interdisciplinary resources to help farmers navigate the numerous publications online and provide timely, science-based education and information to support prosperous farms and healthy farm families.

Farmers have a deep connection with the land they farm and if that’s lost, it can be hard emotionally, said Dr. Jon Moyle, University of Maryland Extension poultry specialist.

“They’ve known that farm their whole life, before they met their spouse even,” he said.

While it’s often touted for its stability in cash flow and year-round income, commercial poultry farming is not without stress. Moyle said the industry’s trend to production without antibiotics has increased bird mortality rates and for longtime growers who are not accustomed to losing as many birds, it has an effect.

“We’re seeing more stress symptoms in our growers,” he said. “Our older generations, it seems to me, they’re more stressed about it.”

With so much out of a growers’ control from weather or the spread of disease, Moyle said the loss of farm assets, as some farmers in the Carolinas have experienced from Hurricane Florence, can carry an even greater weight.

“When you feel helpless and you’re watching your stuff go away, it’s tough,” he said.

Access to affordable and effective health insurance and care is one of the top concerns among farmers who are often self-employed. Providing health insurance, disability coverage, and planning for retirement and long-term future care have also proven problematic. In fact, in a USDA-funded study, 45 percent of farmers were concerned that they would have to sell some or all of their farm to address health-related costs.

The new web pages — split into three categories: financial resources, stress management and legal resources — offer information on how to manage farm stress through a variety of subject areas including financial management, legal aid, mediation, stress and health management, and crisis resources for families dealing with depression substance abuse, mental health concerns.

“There’s a lot of different things from around the country. We can’t reinvent the wheel but we can point out what’s available.” Moyle said the web site resources are helpful but looking out for one another, already a hallmark of the farming community, is perhaps the best way to work through stressful situations.

“I think we all just need to work together. You know who your friends are, keep an eye on them,” Moyle said. “It’s what we should be doing anyway.”

Farmers are facing the decision to parcel off their land, file for bankruptcy, and take secondary jobs off the farm to provide supplemental income.

The University of Maryland Extension last month launched a new web page devoted to assisting farm families in dealing with stress management through difficult economic times. The Farm Stress Management website, located at https://extension.umd.edu/FarmStressManagement, was released in conjunction with National Suicide Prevention week on Sept. 9-15.

It is a set interdisciplinary resources to help farmers navigate the numerous publications online and provide timely, science-based education and information to support prosperous farms and healthy farm families.

Farmers have a deep connection with the land they farm and if that’s lost, it can be hard emotionally, said Dr. Jon Moyle, University of Maryland Extension poultry specialist.

“They’ve known that farm their whole life, before they met their spouse even,” he said.

While it’s often touted for its stability in cash flow and year-round income, commercial poultry farming is not without stress. Moyle said the industry’s trend to production without antibiotics has increased bird mortality rates and for longtime growers who are not accustomed to losing as many birds, it has an effect.

“We’re seeing more stress symptoms in our growers,” he said. “Our older generations, it seems to me, they’re more stressed about it.”

With so much out of a growers’ control from weather or the spread of disease, Moyle said the loss of farm assets, as some farmers in the Carolinas have experienced from Hurricane Florence, can carry an even greater weight.

“When you feel helpless and you’re watching your stuff go away, it’s tough,” he said.

Access to affordable and effective health insurance and care is one of the top concerns among farmers who are often self-employed. Providing health insurance, disability coverage, and planning for retirement and long-term future care have also proven problematic. In fact, in a USDA-funded study, 45 percent of farmers were concerned that they would have to sell some or all of their farm to address health-related costs.

The new web pages — split into three categories: financial resources, stress management and legal resources — offer information on how to manage farm stress through a variety of subject areas including financial management, legal aid, mediation, stress and health management, and crisis resources for families dealing with depression substance abuse, mental health concerns.

“There’s a lot of different things from around the country. We can’t reinvent the wheel but we can point out what’s available.” Moyle said the web site resources are helpful but looking out for one another, already a hallmark of the farming community, is perhaps the best way to work through stressful situations.

“I think we all just need to work together. You know who your friends are, keep an eye on them,” Moyle said. “It’s what we should be doing anyway.”